Disturbing Things That Never Made It Into Oppenheimer

Over the course of its mammoth three-hour runtime, Christopher Nolan's "Oppenheimer" paints a pretty clear picture of the man with his name on the marquee. Neither condemnation nor redemptive biopic, it's a full image of Robert J. Oppenheimer (Cillian Murphy), following him all the way from his training in quantum physics to his work leading the Manhattan Project and the years after World War II. Everything from his troubled younger years to the security hearings that ousted him from Washington is covered. However, there are still a lot of details that the movie leaves out.

In a story of this scale, that's inevitable. "Oppenheimer" sports a gargantuan cast, with tons of big-name actors only getting a couple of scenes each due to how crowded the plot is. Nolan alludes to a number of interesting threads over the course of the film that just don't have time to be fully explored. There are also some big storylines surrounding the Manhattan Project that the movie doesn't even begin to get into.

Of course, because of the subject matter, many of these missed opportunities are pretty grim in their own right. Nothing about the development of atomic weapons is happy, nor should it be. As such, there are a lot of disturbing things that just never made it into "Oppenheimer" at all.

The bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki

The most obvious exclusion in "Oppenheimer" is any actual depiction of the atomic bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. But if you think about it for even a minute, you'll likely come to understand why Nolan and his team opted to keep these events off-screen. The mass murder of innocent civilians perpetuated by the United States in Japan is sickening, and the film treats it with the gravity required. However, going so far as to show the bombings may not have accomplished much beyond shock value.

Threading the line between honest depiction and gratuitous dramatizing is tough. Is there an argument to be made that some actual scenes of the bombings would help drive home just how vile they were? Perhaps. But again, walking that line would have been a difficult — and perhaps impossible — task. Nolan clearly decided it wasn't something he wanted to tackle in this film, so instead of crafting a controversial reenactment, he chose to convey the effect of the bombings in other ways.

Even so, that effect can't be understated. "I think the atomic bombings were one of the two greatest crimes against humanity in the 20th century, along with the Holocaust," former Nagasaki mayor Hitoshi Motoshima said in 1995 (via The New York Times). What the film doesn't show is just how powerfully the shockwaves of the bombings are still felt in Japan today.

Was Jean Tatlock actually murdered?

Jean Tatlock (Florence Pugh), with whom Oppenheimer has a longstanding affair, plays a relatively small but incredibly important role in "Oppenheimer." Jean's suicide is a major moment in the story, giving the physicist a glimpse of what it's like to feel responsible for innocent death. What the film doesn't get into — probably for the best — is that Tatlock's death has been the subject of some big conspiracy theories.

According to the book "An Atomic Love Story: The Extraordinary Women in Robert Oppenheimer's Life," Tatlock's autopsy found traces of chloral hydrate in her body — a compound often used at the time in combination with alcohol to render a person unconscious. Other circumstances surrounding her death, such as the non-fatal dose of barbituates in her system and the fact that her suicide note was left unsigned (noted in the movie), have led some to question whether or not Tatlock may have actually been killed.

Even more wild are the theories concerning who could have wanted her dead. Since she was a known and outspoken communist, it's no secret that the U.S. government would have been keeping tabs on her activities. And since her affair with Oppenheimer continued during the Manhattan Project, it's speculated that she could have been seen as a security liability. These theories have never been proven, but they are an interesting piece of the story that "Oppenheimer" leaves out.

If you or someone you know is struggling or in crisis, help is available. Call or text 988 or chat 988lifeline.org

Kurt Gödel's gruesome death

Unless you're a World War II history buff or an expert on the lineage of modern logic and philosophy, you might not have even noticed that Kurt Gödel appears briefly in "Oppenheimer." A famous logician, Gödel (James Urbaniak) features in the scene where Oppenheimer consults Albert Einstein (Tom Conti) in the woods about the dangers of an atomic detonation.

Einstein remarks that his friend Gödel, who was forced to flee Nazi occupation in Austria, is still terrified that German spies will try to poison or assassinate him in America. This was true of the real Gödel as well. To try to assuage his fear and paranoia, and because of a series of digestive problems, he had his wife Adele prepare or taste most of his meals. After she was hospitalized from a stroke in the late 1970s, however, she was unable to fulfill these duties. As a result, Gödel effectively starved himself, still terrified of being poisoned and dealing with a number of mental and physical health problems. He died from this self-starvation and malnutrition in 1978, with his wife ultimately outliving him.

While Gödel's grim story would have been a bit of a tangent in "Oppenheimer," it shows just how powerful the Nazi machine of fear and violence was. Even when he was safe on the other side of the world and decades after the death of Adolf Hitler, the esteemed logician couldn't escape the scars that the Nazi regime had inflicted on him.

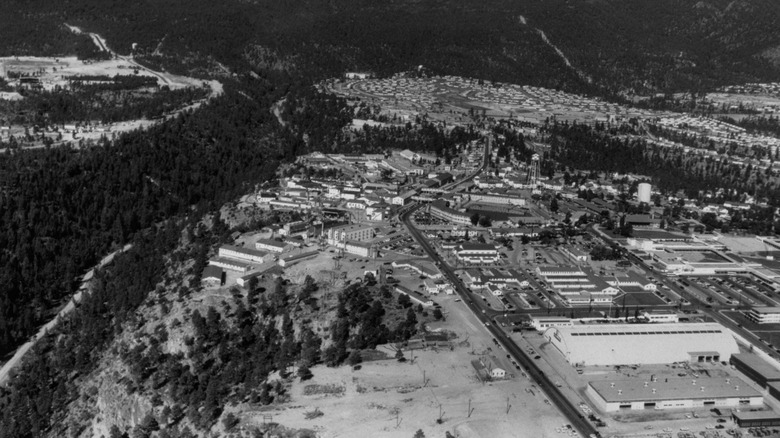

The Trinity Downwinders

The Los Alamos facility depicted in "Oppenheimer" was intentionally constructed in a remote area of New Mexico. However, that didn't stop the fallout from the Trinity test from leaking out into the surrounding areas of the state. Because the U.S. government was determined to maintain absolute secrecy for the Manhattan Project, no nearby ranchers or residents were warned of what was coming. The explosion from Trinity was visible for miles around, but in the wake of the test, the government claimed it was simply an ammunition accident.

The reality is much darker, of course. Radiation from the test seeped into food and water supplies in neighboring communities, leading to a series of serious medical problems in the counties of Lincoln, Socorro, Otero, and Sierra. However, because of the secrecy surrounding the project and the reluctance of government officials to take accountability, the so-called Trinity Downwinders struggled for decades to acquire adequate compensation.

Heart disease and various forms of cancer became highly prevalent in these areas as a result of the test, killing locals who had no way of preparing themselves. Frequently forgotten in larger discussions of the Manhattan Project, the Trinity Downwinders are yet another group of innocents whose lives were irrevocably changed by America's insistence on a nuclear weapons program.

Boris Pash may well have done many deplorable things

Boris Pash (Casey Affleck) is one of the more villainous key characters in "Oppenheimer" — an intelligence officer determined to root out any semblance of communist activity surrounding the Manhattan Project. In one scene, General Leslie Groves (Matt Damon) warns Oppenheimer that Pash is downright vicious in his hatred of communism, and that he'd previously suggested highly immoral forms of interrogation, including off-the-books torture and executions.

Pash's activity during World War II is represented pretty accurately in the film, but his activities after the end of the war may well have involved some of the things Groves mentions in the movie. From 1949 to 1952, Pash worked for the CIA, specifically as the head of Program Branch 7 (PB/7 for short). The official purpose of PB/7 was vague, as it served as a "catch-all" for any espionage or counterintelligence duties not directly assigned to other branches. According to an official U.S. Senate report from 1976, the group may have also been responsible for potential assassination and kidnapping operations.

Though Pash denied this kind of wetwork being under his jurisdiction, his deputy chief claimed the contrary, stating that PB/7 was directly responsible for "assassinations, kidnapping, and such other functions as from time to time may be given it ... by higher authority." This only backs up the film's portrayal of Pash as a brutal man with very few moral limits.

Several Manhattan Project scientists died of radiation poisoning

If you reach the end of "Oppenheimer" thinking how miraculous it is that no Manhattan Project scientists died of radiation poisoning, well, we've got some bad news for you. "Oppenheimer" is full of small details from the real history, but it leaves out several gruesome instances of how dangerous building the bomb really was.

According to the U.S. Department of Energy's official Manhattan Project archive, several workers were exposed to intense radiation while working with the uranium, though none died. In an ironic twist of fate, the project's first radiation fatality came after the end of the war, when Harry K. Daghlian dropped some materials and ended up dying weeks later. In 1946, another death came to the still-operating facility when physicist Louis Slotin also dropped fissionable materials and received a heavy dose of radiation.

These instances may have been omitted from the film simply because the most fatal ones took place after the war. However, they still speak to the dangers of working with nuclear materials and the inherent risk of being the first people ever to experiment with such technology.

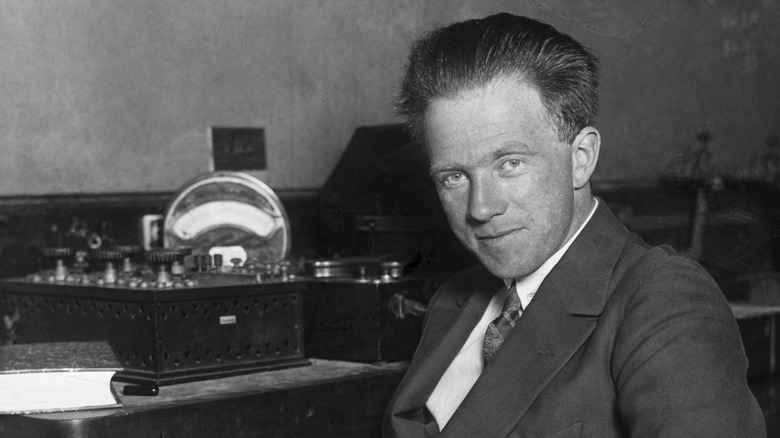

Werner Heisenberg's Nazi legacy

Werner Heisenberg (Matthias Schweighöfer) only appears in one scene in "Oppenheimer," years before the rise of Hitler's Nazi regime in Germany. Oppenheimer meets him during his training in Europe, and we're later told how he winds up leading Germany's own atomic weapons program. Like many other German scientists in World War II, Heisenberg avoided consequences for his contributions to the Nazi war machine. He went on to hold a number of prestigious scientific positions after the war.

In his later years, Heisenberg claimed that he helped drive German research and development away from weapons specifically, as he objected morally to the use of an atomic bomb. In more recent times, some historians and journalists have claimed that Heisenberg even helped leak information about secret Nazi research to the Allied powers. How true all of these claims are has been a subject of extensive debate for years, but there's an undercurrent to them that gets more uncomfortable the more you look at it.

Heisenberg is the kind of person that history wants to exonerate. It would be much cleaner if we could just focus on his Nobel Prize years and remember him as a trailblazer in the field of quantum physics. The problem is that there's a whole campaign of Nazi conquest, oppression, and genocide in there too. "Oppenheimer" doesn't spend much time on this part of Heisenberg's life, which makes sense given his relatively minor role, but it's still a messy part of the history that's well worth reiterating.

How the Manhattan Project stole and devastated Native American land

"Oppenheimer" briefly mentions that the area of and around Los Alamos was sacred, ancestral land for local Native American tribes. After the end of the war, Oppenheimer recommends that President Harry S. Truman (Gary Oldman) give the land back to its original Indigenous inhabitants. Of course, by that time, the whole area was already changed beyond repair, because of both the government facilities constructed there and the fallout from the Trinity test.

Los Alamos was home to a number of Pueblo communities prior to the Manhattan Project. The construction of the government facility — one that still remains on the land today — disrupted a long history in the area, preventing traditional patterns of hunting, fishing, and various other rites. Indigenous art and pottery became such a popular fad with the Los Alamos scientists and their families that it fractured the very economy and ecosystem of the Pueblo tribes.

In addition, a number of Hispanic homesteaders in the area were essentially pushed off their land by the U.S. government. They were given no real choice and received far less financial compensation for their acreage than their white counterparts. Today, Los Alamos remains forever changed by these callous imperial actions.

The FBI persecuted gay people during the Manhattan Project

You'd think that in the case of the Manhattan Project, beating the Nazis would be far more important to the U.S. government that the personal lives of individual scientists. But this is the 1940s we're talking about, so you'd be wrong. Recently declassified documents show that communism wasn't the only red flag intelligence officials were looking for at Los Alamos. The FBI also spent immense resources monitoring and investigating those workers suspected of being gay.

Houses and facilities for the Manhattan Project were bugged, and the behavior of workers was constantly being evaluated. A group of women known as the "Manhattan Eight" received particular attention for being suspected lesbians, which later led to the revocation of security clearances. President Eisenhower officially outlawed gay individuals from serving in federal positions in 1953, with queerness widely seen as "subversive" and frequently paralleled with other "anti-American" groups like communists.

Given the sociopolitical climate of the time, this information probably isn't surprising to anyone, but it does show just how invasive the FBI was during this era. For better or worse, working on the Manhattan Project was seen by many as a huge service to America. However, anyone suspected of queer activity — especially women — were treated more as enemies to be distrusted and cast aside than national heroes.

How did Oppenheimer die?

Though the film carries his name, it doesn't follow Oppenheimer all the way to the end of his life. We get a brief glimpse of his final years in a flash-forward that shows him being awarded the Enrico Fermi Award in 1963, but the film doesn't show how Oppenheimer died. In reality, he passed away shortly after that prestigious moment, succumbing to lung cancer on February 18, 1967. He was only 62 years old.

Oppenheimer was a heavy smoker, as depicted in the film by the pipe he always seems to be carrying. In what could be seen as an ironic twist, he received radiation treatment for his condition, seeking healing from the very thing he used to create a weapon of mass destruction. Regardless, the treatment was unsuccessful, and Oppenheimer passed away the next year.

In a dramatized version of his life like Nolan's film, there's something interesting about Oppenheimer's premature, relatively uneventful death. But looked at as part of the larger history, perhaps it's not important enough to include in a movie. After all, he lived a lot longer than many of the innocents his weapon killed.

The tragic fate of Oppenheimer's daughter Toni

Far sadder than Oppenheimer's own fate is that of his daughter Toni, who can be seen in the film as a young child. In 1969, Toni applied for a position as a translator with the United Nations, seeking to contribute to the international diplomacy that her late father had valued so much. However, she was rejected from the position because the FBI refused to grant her the necessary security clearance.

While not explicit, it's widely believed that the main motivator in this denial was simply her relationship to her father. As depicted in the movie, Oppenheimer was stripped of his own clearance in 1954, branded a communist sympathizer by some, and made a national pariah.

In 1977, Toni Oppenheimer died by suicide shortly after turning 32. She retreated from public life after being rejected from the U.N. position and struggled with her mental health for the rest of her years.

If you or someone you know is struggling or in crisis, help is available. Call or text 988 or chat 988lifeline.org